<ROIIC>

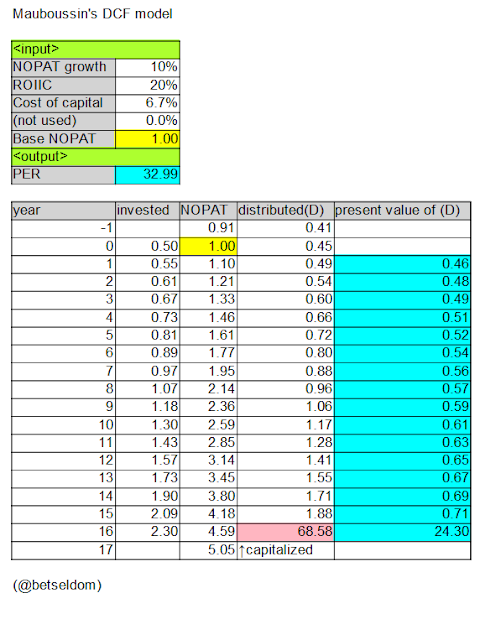

さらにここからは、ROIICの予想値が変化するとどのような影響がでるのか見てみよう。NOPAT(税引後営業利益)成長率が10%と仮定した状況に戻って、異なるROIICを設定することで保証PER倍率がどうなるのか検討していく。

ROIIC. We now turn to seeing the impact of changing assumptions about ROIIC. We’ll revert back to our 10 percent baseline NOPAT growth and consider the warranted P/E multiples assuming different ROIICs.

ここでいったん、文中で登場する用語を説明する文章に移ります。「標準PER倍率(commodity P/E multiple)」という用語についてです。

標準PER倍率(commodity P/E multiple)の基礎的な例から始めよう。この値は「年あたり1ドルの利益を生み出すが、今後は新たな価値を創出しない永久債として扱うべきもの」に対して支払う金額の倍率である。これを求めるには、資本コストの逆数を乗算すればよい。たとえば資本コストが8%であれば、標準PER倍率は12.5になる(1 / 0.08 = 12.5)。

Let’s start with the basic example of the commodity P/E multiple. This is the multiple you should pay for $1 of earnings into perpetuity assuming no value creation. You calculate the multiple by taking the inverse of the cost of equity capital. For example, if the cost of equity is 8 percent, the commodity P/E multiple is 12.5 (1/.08 = 12.5).

以下、本文に戻ります。

図4にその結果を示す。この条件における標準PER倍率が14.9であることに留意してほしい[6.7%の逆数]。それでは考えを進めてみよう。ROIICは、予想成長率を達成するために資金をどれだけ投下すべきかを示している。ROIICが高ければ、成長に対する投資はそれほど必要ではない。つまり、株主に回すことのできる現金が多く残る。その反対にROIICが低いと、成長を果たすための資金が余計にかかり、株主用の現金が少なくなる。

バフェットは、成長することが「好影響になることもあるし、悪影響になることもある」と付け加えた。ROIICが資本コストを下回っていれば、成長は[価値に対して]悪影響を与える。そのような企業は1ドルの資本を費やすことで、1ドル未満の価値を手にいれるのだ。その場合、企業の成長が急速であるほど、より多くの財産が失われていくことになる。

上記の図は「ROIICが資本コスト6.7%に満たないと、株価のPER倍率が標準倍率を下回る」ことを示している。企業買収の例がこれに当てはまる。一般に買収を実現することで、買い手からすれば利益は増加するものの、[企業]価値は下落する。つまり「ROIICの低い投資を実施している企業は、株価倍率を標準倍率へ押し下げている」と、みなすことができるだろう。

Exhibit 4 shows the results. Recall that the commodity P/E is 14.9. Here’s the way to think about it: ROIIC tells you how much you have to invest to achieve an assumed growth rate. A high ROIIC means you don’t need to invest much to grow, which means there’s more cash left over for shareholders. A low ROIIC means you have to invest a lot of capital to grow, leaving little for the owners.

Buffett added that the impact of growth “can be negative as well as positive.” Growth is a negative when the ROIIC is below the cost of capital. In that case, a company is spending $1 worth of capital to attain less than $1 of value. The faster the company grows the more wealth it destroys.

The exhibit shows that an ROIIC below the cost of capital of 6.7 percent yields a P/E multiple below the commodity multiple. Acquisitions are again a case in point. For buyers, M&A deals commonly add to earnings growth but subtract from value. You can think of low-ROIIC investments as pushing down the P/E multiple of a company’s stock toward the commodity multiple.